For some years now, postcolonial and intersectional studies and theories have been increasingly received in social work[1]. This has contributed significantly to the fact that the role of social work in the social reproduction of racist discrimination is increasingly being criticized within the discipline and that - primarily qualitative - studies on racism in social work are carried out. In this context, practices of the construction of racialized „others“ by social work itself, its adherence to the claim of dominance of Western educational and value concepts, the role of social work in development cooperation, asymmetrical concepts of help and addressees, etc. are examined. Furthermore, certain theorizations of social work are also critically examined in a new way in this context. This development is as welcome as it is unavoidable, as it forms the basis for a real dismantling of racist practices and structures within the profession. However, the historical background and continuities of its emergence have hardly been illuminated so far.

The founding of modern social work as a profession coincided directly with the period of Germany's formal colonial rule. In 1893, only a short time after the European colonial powers under the leadership of Reich Chancellor Bismarck had divided up the African continent among themselves and the German Empire had become the third largest colonial power, the girls' and women's groups for social aid work were founded out of the radical wing of the Berlin women's movement. From this union a number of organizations and also methods of professional social work emerged, some of which continue to exist or are still of importance today. Alice Salomon's „Social Women's School“, today's Alice Salomon University of Applied Sciences in Berlin, is a prominent example. Many protagonists in the „first rank“ of social work were also active in the colonial movement and established connections between the social initiatives of the women's movement and colonial organizations.

The different forms of social work participation in the implementation of colonial rule have not yet been systematically researched. Examining these can - in addition to a professional historical yield - provide important answers to the question of whether social work - as former ASH rector Christine Labonté-Roset once put it on the occasion of the discussion of social work's involvement in National Socialist population policy - „has moments that enabled its use as an apparatus of repression and selection“ (Labonté-Roset 1988). For the colonial intensification of the idea of social work as „cultural work“ developed by the women's movement worked not only in the colonies as an instrument of domination, but also in the metropolises themselves. Thus, colonial narratives can be found, for example, in descriptions of the lifeworlds of addressees, who were often assigned colonial attributes by being portrayed as „alien“ and „uncivilized“. Even in contexts of international cooperation within the women's movement and social work, racism and colonialism were not exactly met with resistance. Rather, social work constituted itself as a white space in which Eurocentric notions of social order, education, work, and family life became guiding principles for action.

A look at the radical wing of the Berlin women's movement shows that this was not the only source of initial impulses for social work in Berlin. Minna Cauer (1841-1922), women's rights activist and co-founder of the aforementioned „Girls' and Women's Groups“, advocated the emigration of educated women to the African colonies. She wrote: „There is indeed a field of activity for women here [in colonization, DL]. [... They] would certainly be willing to cooperate in such an important question if they were convinced [...] that their cooperation was counted on from the beginning in solving the cultural tasks in the colonies.“ She specified the „cultural tasks“ as follows: „Past experience has unfortunately proved that barbarism, interest economy, and old-fashioned views have brought about appalling brutalization over there.“ (Cauer 1898). She considers it the task of German women to improve this deplorable state of affairs, completely in the tradition of the social work founding idea of „spiritual motherliness“.

Another example is the entrepreneur Hedwig Heyl (1850-1934), who ran a cooking and housekeeping school in the immediate vicinity of Salomon's social work school and founded the socio-educational youth home Charlottenburg. A nationalist right-wing conservative, Heyl served for 10 years as chairwoman of the Women's League of the German Colonial Society and in this capacity ensured viable links between the various organizations. She saw in women's colonial „cultural work“ not - like Cauer - an opportunity for legal and political equality for women, but the possibility of making a significant contribution to the establishment and expansion of German colonial power and to the preservation of „German culture.“ Inspired by British models, she also dreamed of raising institutionalized children into a new generation of colonists and sending them to the colonies:

„I had been deeply impressed by Bernardo's [sic] children's home in England. The same educated especially illegitimate children to become settlers and helpers in the English colonies; the methods closely followed my aspirations realized in the Jugendheim“ (Heyl 1925).[2]

Heyl created a dense, efficient network of colonial organizations in the colonies - mainly in the so-called „German Southwest“ in the area of present-day Namibia - and in the metropolis of Berlin, which sent socially and housekeeping-prepared white German women to the colonies. These women were tasked with maintaining and promoting „Germanness“ in the colonies. This included, among other things, socio-educational work with the children of the white settlers. For this purpose, a youth home was founded in Lüderitzbucht based on a Berlin model. According to the propagandist of the Women's League of the German Colonial Society, Else von Boetticher, this home served to „create a gathering place for the small children of the German population, who were not very well supervised by their mothers who were busy with housekeeping, and to teach them the ways of the homeland and German customs“ (Boetticher 1914). In addition, the home provided immigrant German women with lodging for their transit and a regular gathering place. In this way, a „haven of German character“ was to be created.

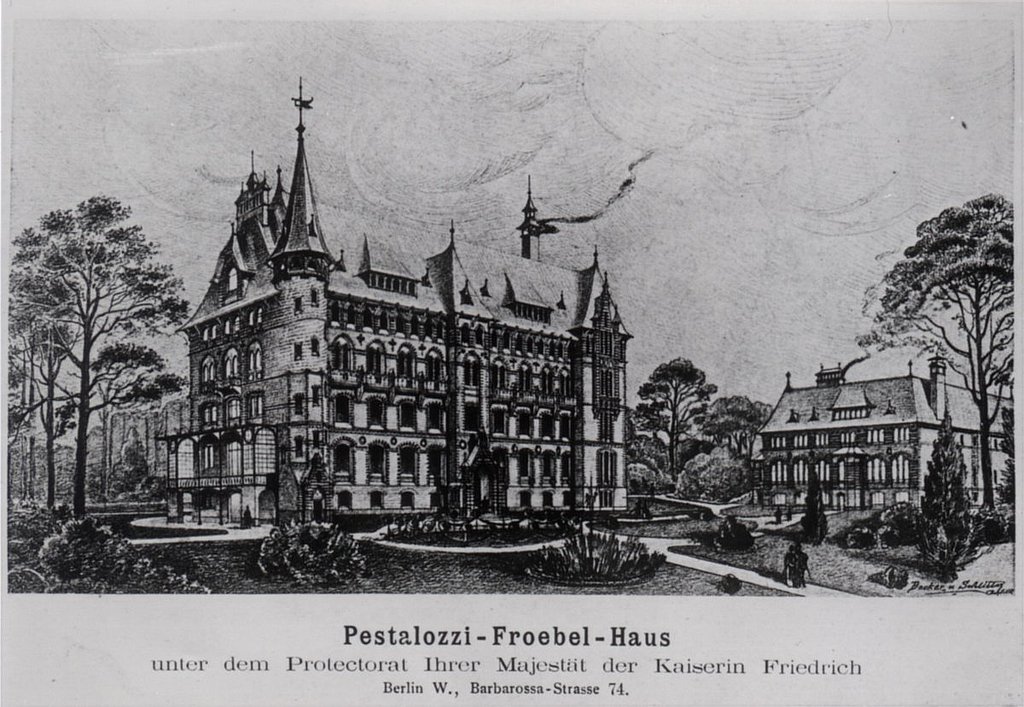

This understanding of social work as colonial and national cultural work had profound consequences for the development of the profession. Therefore, it is also relevant for the present of social work to ask how this was handed down within the profession, whether and how it was broken or which alternatives were set against it. These questions are addressed by the Alice Salomon Archive of the ASH Berlin together with cooperation partners from the Pestalozzi-Fröbel-Haus Berlin, the Universities of Hildesheim and Marburg and the Rhine-Main University of Applied Sciences in a BMBF-funded research project with a duration from 01/01/2023-12/31/2026. The project is particularly concerned with reviewing the role of Berlin social work initiatives in German colonialism and analyzing forms of (re)production of colonial and racist knowledge in historical sources of early social work. At the heart of the study is a series of teaching research projects conducted in degree programs at the participating universities and colleges. In these, the source studies will be supplemented with surveys of the colonial racist presence of (social) pedagogy and social work, and the findings of these studies will be related to one another.

Information about the project

Project name: „Social work as a colonial knowledge archive? A history laboratory on the (post-) colonial heritage of social work as a model of historiographical teaching research“

Project duration: 01/01/2023 to 12/31/2026

Project management: Dr. Dayana Lau

Funded by: Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Directive „Current and Historical Dynamics of Right-Wing Extremism and Racism“

Project partners: Sabine Sander and Silke Bauer, Pestalozzi-Fröbel-Haus Berlin; Dr. Z. Ece Kaya, University of Hildesheim; Prof. Dr. Wiebke Dierkes, Rhine-Main University of Applied Sciences; Prof. Dr. Susanne Maurer (retired), University of Marburg

Website: https: //www.alice-salomon-archiv.de/projekte/

References

- Boetticher, Else von (1914): The Heimathaus in Ketmannshoop and the Jugendheim in Lüderitzbucht, the Adda-v.-Liliencron Foundation. Berlin. (brochure)

- Cauer, Minna (1898): Zur Frauen-Kolonisationsfrage, in The Women's Movement, 4 (7): 77-8.

- Heyl, Hedwig (1925): Aus meinem Leben, Berlin: Verlagsbuchhandlung Schwetschke & Sohn.

- Labonté-Roset, Christine (1988): Preface. In: FHSS Sonderinfo May 1988, pp. 1-3.

- Liebel, Manfred (2016): Colonial and postcolonial state crimes against children. Discourse Kindheits- und Jugendforschung /Discourse. Journal of Childhood and Adolescence Research, 11(3), 363-368.

[1] Here and in the following, the now common version of social work refers to both social pedagogical and social work professions.

[2] The children's homes of Thomas John Barnardo (1845-1905), founded in England from the mid-19th century onwards, were part of an organizational network that deported a total of up to 150,000 children, who were socially considered „useless“ to the British colonies until the 1970s - as cheap labor and as white colonists, they served, as it were, as „building blocks for the Empire“ (Liebel 2016, p. 364).